Art, education, protest, leadership: Latinos leave their mark on the city over the years

By Melanie Slone

In 1979, after giving a speech at Palomar College, Cesar Chavez ate dinner at John Valdez’s home, where he held Valdez’s toddler son on his lap.

John Valdez remembers that story well, like so many others anchored in the city of San Marcos. Valdez was a Chicano Student Movement of Aztlán (MEChA) historian at UCSD La Jolla. His first time in San Marcos was at a MEChA protest in 1971.

In 1971, “I came with the president to Palomar in my beat-up VW. As we came into the parking lot, we ran into a whole range of protestors… We just joined the march,” he told North County Informador.

San Marcos was a different place back then.

“MEChA was extremely powerful and active throughout the county. And they called for a protest on behalf of the MEChA students at Palomar.”

Valdez remembers that the school administration had left, and Dr. Theodore Kilman was the only one who remained, speaking to the students in the cafeteria.

“The protest was a march through the plaza,” he remembered.

He says the movement brought thousands of high school students to the campus over five years—from Encinitas, Fallbrook, San Marcos, Escondido, and Vista.

“We had big events, busloads of students. Some of the people on campus that worked for the college were not happy seeing so many Mexicans, Latino students,” he added.

The fight for Latinos in education gained strength during those years, and San Marcos, especially Palomar College, played a leading role.

The birth of Chicano Studies

Back in the 1950s and 1960s, said Valdez, Latinos did not enjoy many educational opportunities.

“They didn’t really educate you for college. You were being trained, vocational arts,” he said.

Valdez was able to get a classical, pre-philosophy, spiritual training to become a priest at University of San Diego, after having felt excluded at the high school level.

Four years later, he realized he wanted a family, so he shifted gears and went back to USD, and later to UCSD.

“There were so few Latinos at UCSD. There were only about 12…Only two graduated one year, two Latinas in the early 70s,” he remembers.

At UCSD, Valdez found his true calling. “We’re creating basically Chicano Studies,” he said. “I have to get my hands on books, go to conferences, learn the subject…they didn’t have these classes. We were pioneers…putting these classes together.”

He says the class offerings he helped design were unique at the time—African Studies, Chicano Studies, Multicultural Studies, Judaic Studies, Asian Studies… “But it was a struggle,” he said. “It was controversy. One controversy was the union, the Farmworkers’ Union. César Chávez. We wholeheartedly supported the UFW, the Farmworker Union. We would picket Safeway, boycott lettuce, wine, grapes.”

These protests led him to Palomar and San Marcos in 1971.

The struggle for a place

“The first time I arrived in San Marcos was through the back country. I thought, where is it?… Rural, open fields, maybe a cow here, a cow there…”, Valdez told us.

“But we found Palomar, and we were united, we were focused, and we were energetic,” he added.

“There was a lot of resistance to us,” he says. “We were lowering the standards, we were bringing the ghetto, we were bringing the barrio to beautiful Palomar.”

The city of San Marcos would be the site of the showdown.

“San Marcos really was a very rural, very quiet… It was open fields, and there were some small stores. But there was an office building with a huge Mexican flag. And it was the off-campus MEChA office in this field.”

Valdez explains that this MEChA room was the main heart of Palomar for Latinos and Chicano Studies. And the Latino presence was beginning to be felt off campus as well.

“I remember driving off the 78,” he said. “You go through San Marcos, then you go over the hill, to the backroad… I remember driving to Encinitas… no buildings. No houses. Open, beautiful hills. Just no houses at all in the 70s. Nothing. I remember when I reached Encinitas, there was a farm, and there was an Emiliano Zapata poster, with his rifle, right there, off the road. I thought, well, this is amazing to see an Emiliano Zapata poster in Encinitas off El Camino Real.”

The 1980s

Valdez remembers when the Cal State San Marcos campus was being built, in the 1980s. “The Latino population was present,” in the city, he said. “It wasn’t organized. There were no groups.”

The early 1980s brought more controversy with a mural at Palomar campus.

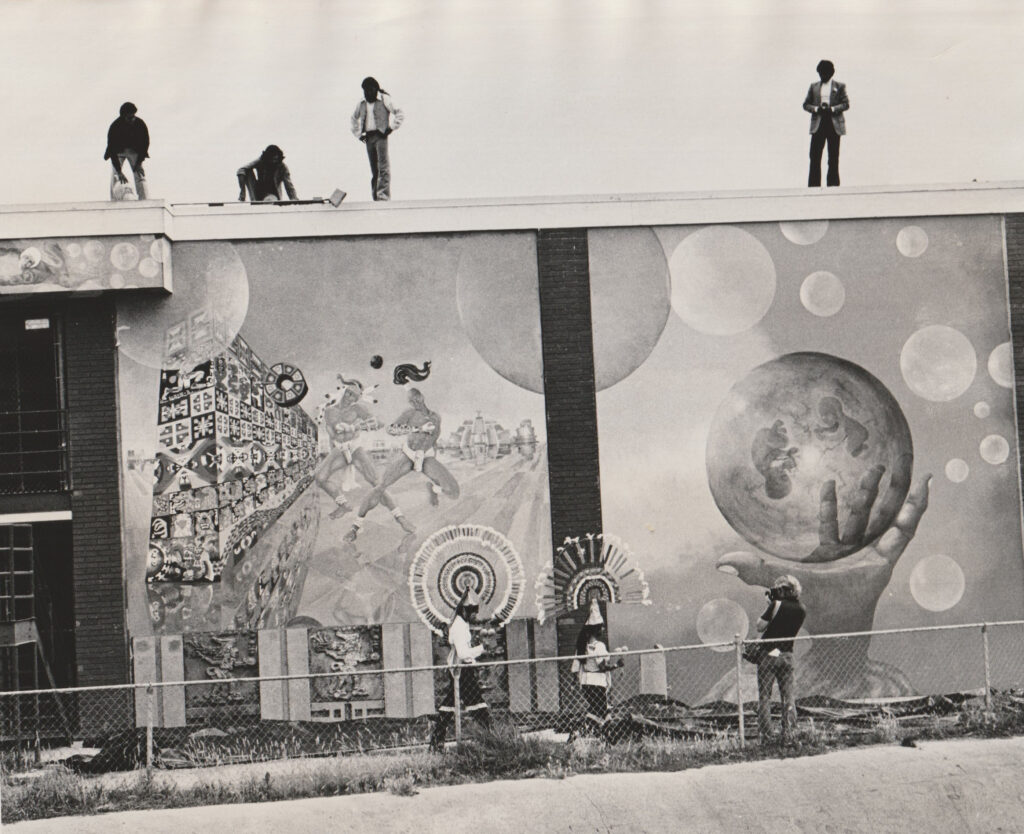

“One of the first major contributions from our students was a mural on Cinco de Mayo, 1980…The first major mural in North County by our students as an artistic, intellectual contribution to the college…”

The response was, “we don’t want this mural…It’s going to detract from the beauty of Palomar. It’s going to draw graffitists and put their marks on the wall.”

Still, the artists Edgar Olivares, George Papciak, and Manuel Sepulveda created a four-paneled MEChA mural on a wall of the campus racquetball courts. Valdez called it “Spherical Transformation.”

But things would get harder for Latinos in San Marcos.

The 1990s

In the early 1990s, there was a rash of shootings. A high school student was shot sitting at the bus stop and another at a home in San Marcos.

To face this threat, MEChA called for a meeting of the communities. “The sheriff came, some parents came, and a priest came,” he said.

It was then that Vince Andrade stepped up in San Marcos. He was also elected to the City Council, where he served until his death from cancer in 1999. His voice stood out in defense of the Latino and Spanish-speaking communities in the city.

“Vince Andrade came up as a leader, concerned about what was happening among the youth. We started some Boy Scout troop for Latinos, for Spanish-speaking Boy Scouts,” remembers Valdez.

“Vince Andrade came out as a leader for the concern of what was happening in the community among the youth,” said Valdez. “The threat went away over time, thankfully.”

The 2000s

The Latino struggle for a place in San Marcos continued into the 2000s, when the resistance began to back down some, according to Valdez. “That’s a long time we had to battle our situation,” he says.

When a new dean came on, “He speaks for us. He doesn’t like to hear degrading comments about our department,” he explained.

“Since then, we have another mural. I was inspired to call it ‘Adelante, MEChA, adelante’. Forward, MEChA, Forward,” says Valdez.

This second mural is located in the homeroom of the Multicultural Studies Department and MEChA. Valdez says it represents a new generation of students.

The original mural from 1980 is still on campus. Valdez, who retired in 2015, hopes another will be painted soon, “to have a trilogy” and continue to preserve the Latino and Chicano history and culture from the area.

San Marcos today

Today, Palomar College has come a long way from those days of protest, boasting its first Latina president/superintendent, Star Rivera-Lacey.

Valdez says having a Latina president of Palomar “is absolutely glorious. She’s such a wonderful person, and we support her 100%. It’s not easy being a leader…”

He says there are other community leaders today.

“I see great potential,” he says. “These kids are getting a good education. They have dedicated teachers.”

What advice does Valdez have for Latinos in San Marcos today?

“Be patient,” he says. “Trust your feelings. Continue to dream; ask questions. Believe in yourself. Appreciate all those that love you. And do the best you can. Read. Strive to learn. Help the community. Help your family. And have faith in your future.”

He is hopeful for that future. “When [Andrade] passed, we didn’t really have a leader. But now we have María Núñez [of Universidad Popular], the new generation. Articulate, smart. And the whole family, Arcela Núñez…They get along with people” he says.

“And they love San Marcos. A great combination.”