Follow her journey from housing insecure to housing advocate, educator, and racial justice warrior

By Melanie Slone

“If you don’t have a seat at the table, you might be on the menu. And if there is no table, don’t be afraid to create your own,” says Beatriz “Bea” Palmar, who has followed her own advice.

Bea’s parents worked in the fields, and her father struggled with addiction. “We were often housing insecure. By the time I reached high school, we had moved probably 25 times.” Yet, she never considered herself as homeless. “Until you learn that homelessness is also housing insecurity. And we were very housing insecure,” she says.

“Education, while it may not be the solution to everything, propels us forward to break through a lot of those symptoms of poverty,” she adds.

Planting the Seeds in Education

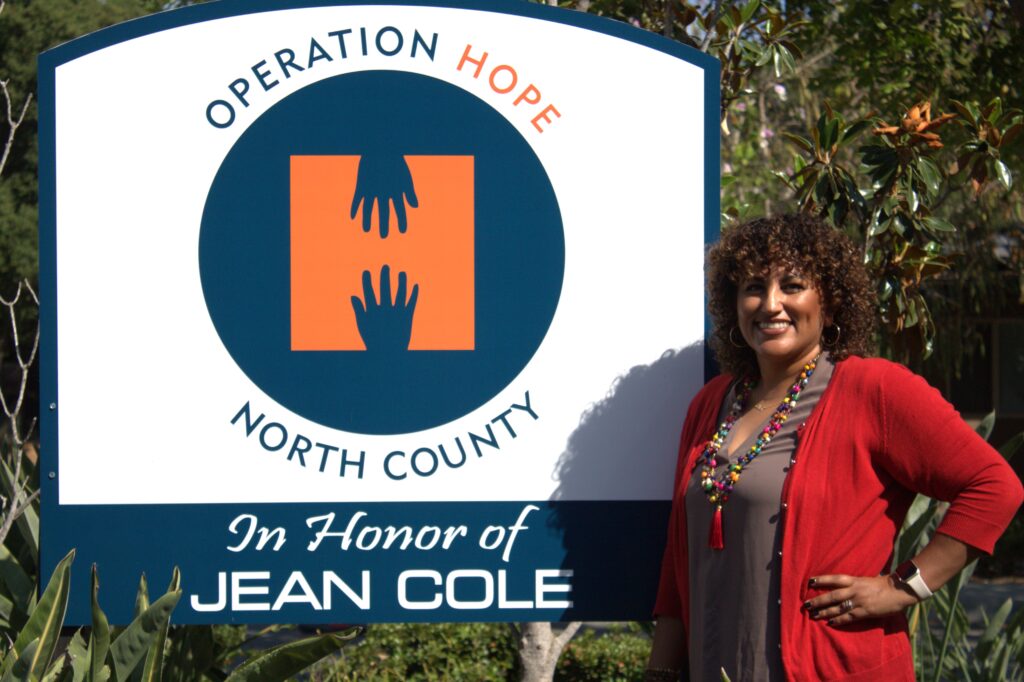

Bea came to the United States with her family from Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, before she turned two. Today, she is the acting executive director at Operation Hope-North County and the director of the Federal Grant for Full-service Community Schools with National University’s Sanford College of Education.

Bea is grateful for the assistance she received through Migrant Education. She remembers when she was in high school and Señora Sara Rivera, the mother of Palomar College’s current president and superintendent Dr. Star Rivera-Lacey, visited her mom. “She said, Beatriz is not finishing her homework. And she sat at the foot of my bed. She brought me the book and she would not leave until I read chapters and got some writing done.”

Bea is grateful for Mrs. Rivera and for many other counselors who helped her become the first in her family to graduate from high school.

After dropping out of MiraCosta, she eventually returned there to work. Her boss at the time, Dr. Carol Wilkinson, encouraged her to go for her degree.

She and her husband went back to schools as adults, “and that’s how we were able to get our family out of poverty,” she says. “We were housing insecure. We were actually homeless. My mom took us in,” she remembers. “We were able to purchase our home through the VA and because we had an education that allowed us to have jobs that paid a little more.”

At MiraCosta, Bea began doing classroom presentations and helping place students for service work in the community. “I knew how to do that. I felt really confident because I’m a product of the community,” she says. Eventually, she became the program manager for the service learning and volunteer program.

She later completed her bachelor’s degree, and then a master’s in sociology, which allows her to teach the subject. “When I have to teach about inequality and systems of oppression and the structures of our society, I know it because I come from a disproportionately impacted community.”

Operation Hope

Having gone through housing insecurity, Bea says her work with Operation Hope is dear to her heart. “Operation Hope is a year-round shelter for families with children and single women who are experiencing homelessness…families that grow up with housing insecurity carry a lot of trauma,” she says.

Families at Operation Hope work with a case manager to craft small, measurable goals. “Maybe a family doesn’t have an identification. Maybe the children aren’t enrolled in school. …They start attending parenting classes, financial literacy classes, and then they set other goals, personal goals, professional goals,” Bea explains. They can also get connected with a mental health provider and with job training.

“If we really think about it, most of America is just a few paychecks away from being in the same situation that the families at Operation Hope North County fall into,” says Bea, adding that friends may not even realize it when someone is housing insecure. “They could be the kids who your kids go to school with. They could be somebody at church….63% of our clients on most nights are children and youth.”

As with all nonprofits, Operation Hope, which is a high-barrier shelter, suffers from a lack of funding, getting only 35% from the government. “If the father or the mother is actively in drug addiction, we can’t take them. We want to provide a safe shelter,” Bea explains.

“It is hard work, but it’s such a great feeling to know that you’re part of an organization that isn’t just providing shelter but also a safe place for them to lay their head down and know that they’re safe.”

Bea talks about the increase in homelessness, particularly the growing trend among seniors. “They’re calling them the gray tsunami or the gray wave.”

And there are many children. “Families don’t have access to affordable housing, which is why our cities need to focus on developing truly affordable housing for families and for our elderly.”

Meanwhile, Operation Hope address homelessness holistically. People can keep their jobs and continue attending school while in the shelter. “That’s how they’re going to push through the symptoms of poverty, through education,” says Bea. “I know that’s what helped me.”

Moving forward together

Bea is very involved in racial and social justice initiatives. In January of this year, she was the first Afro Indigenous Latina recipient of the Oceanside Martin Luther King Community Service Award.

She says one in five Latinos has roots in Africa. “When you’re a Black Latina, sometimes it’s a struggle to fit in even within your own community. We have a lot of work to do. Just like there’s colorism within the Black community, we have colorism within the Latino community,” she says. “I hope that through education, through community engagement, we can start breaking down those stereotypes.”

As the chair for women with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the North County, Bea fights to expose people to culture, different ethnicities, and diversity. “This is one of the oldest civil rights organizations in the United States,” she says.

The word Colored in the organization’s name doesn’t just stand for Black African Americans. “Thanks to the work of the leaders of the NAACP, Latinos have the right to vote, women have the right to vote, our LGBT community has rights. “Dr. King did a lot of work with César Chávez…We have to work and move together,” Bea adds.

Tips for Others

Bea has a favorite saying: “Don’t forget where you came from, but never lose sight of where you’re going.” Following that advice, she says she never forgets the sacrifices her parents made living undocumented and not knowing how to read and write. “Those are the stories that give hope to other people.”

She encourages everyone to use their voice for power. “Speak up. And if you speak two languages, be proud of your heritage. Be proud of your identity. And don’t be afraid to learn about others so you can dismantle your own stereotypes and grow as an individual.”

She encourages everyone to dream big and find mentors. “Surround yourself with people that are going to encourage you and push you forward and open doors for you.”

Education is at the forefront for Bea. “If my mom had been afforded an opportunity to pursue her education, she would’ve been a business owner or a scientist, she knows soil and agriculture so well. And my father was a mechanic. And I think, he would’ve been an engineer.” She encourages all adults to take any courses they can. “Learn something new because that’s what going to help break down the generational trauma and poverty and help us leave a stronger legacy for our families.”

Finally, Bea is grateful for everyone who has helped her along the way. “I couldn’t have done it alone,” she says. “Build alliances. Build community with others because that’s what’s going to help you break through some of those barriers.”